The data center boom has catapulted Virginia into a serious energy crunch. We have more data centers here than in any other state, by far, and four times as many more are expected in the next few years. Virginia utilities don’t generate enough electricity to serve them all; fully half of our power is imported from the regional grid. But now the regional grid is also running low on reserve power thanks to all the data center growth, according to grid operator PJM.

Most proposed solutions focus on the supply side: generating more power by building new solar, wind, gas and battery storage; keeping aging power plants running that were previously scheduled for closure; and even reopening Three Mile Island, shuttered three and a half decades ago following the worst nuclear accident in US history.

More nuanced solutions involve managing the existing generation better. Research shows that the grid could handle more data centers right now if operators ratcheted back consumption at peak times, either through installing batteries or through shifting some operations to non-peak times.

All of these approaches involve generating more power for the grid, or shifting use around to relieve grid stress at peak demand times. But there is another way to make room for new data centers: remove some existing loads.

A national advocacy organization, Rewiring America, recently released an intriguing proposal to free up grid capacity by retrofitting homes with high-efficiency heat pumps, heat pump water heaters, solar panels and energy storage. The cumulative effect would be to reduce total demand in the residential sector, making capacity available to data centers sooner, while also saving the participating residential consumers thousands of dollars on their electricity bills.

Oh, and the tech companies are going to pay for it.

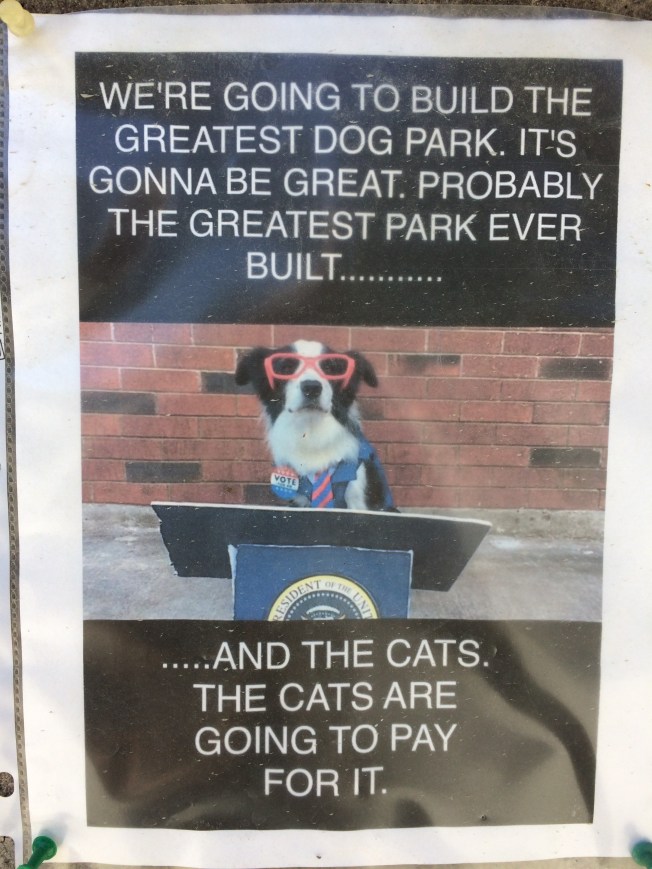

I am reminded of a delightful sign I once saw announcing the coming of the best dog park ever, to be paid for by cats, itself a satire of a certain president’s pledge to build a border wall paid for by Mexico. But, I notice, neither the cats nor Mexico have sent checks yet. Will Big Tech?

Rewiring America thinks so, if the policies are in place to aggregate and verify the household energy savings into a marketable package, and if buying the package means a data center can come online faster and more cheaply. Upgraded appliances and rooftop solar can be installed in a matter of weeks, compared to the many years that may be required to permit and build new generation and transmission.

Note that the proposed program would not include households that replace gas, propane or oil furnaces with heat pumps. That kind of upgrade results in greater, not less, residential electricity demand, making it counterproductive when the point is to shrink residential electricity usage.

Replacing electric furnaces with heat pumps would also mainly address the grid’s winter peak, not its summer peak, though the Department of Energy maintains that heat pumps use less energy for cooling than stand-alone air conditioners.

Researchers focused on replacing electric resistance heat with heat pumps because that one swap produces the biggest efficiency bang for the buck. An electric furnace is cheap to install but expensive to use; the reverse is true of a high-efficiency heat pump. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) estimates that the conversion would save the average family $1,170 per year on its electricity bill. NREL calculates that heat pumps are cost-effective enough to pay for themselves in under 5 years.

According to Rewiring America, “If hyperscalers paid for 50 percent of the upfront cost of installing heat pumps in homes with electric resistance heating, they could get capacity on the grid at a price of about $344/kW-year — a similar cost to building and operating a new gas power plant, which currently costs about $315/kW-year.” (By my math, it’s an extra 10%, which might be acceptable to a power-hungry tech customer as a sort of rush fee.)

The report repeats the calculations for other technologies. Ductless heat pumps would replace baseboard electric heat. Heat pump water heaters would replace conventional electric water heaters. Solar panels paired with battery storage could displace electricity the home would otherwise draw from the grid.

Further capacity could come from home batteries. The report posits, “If every single-family household in the U.S. installed a home battery, and those with a suitable roof installed a 5 kW solar system (about 11 solar panels), they could collectively generate 109 GW of increased capacity on the grid.We assume that households charge the battery off-peak, either from the grid or from rooftop solar, and they discharge the battery during peak periods to reduce the household’s contribution to peak demand.”

The researchers estimate that a mass purchasing program could squeeze costs of solar and storage down by 40%, primarily through reduced customer acquisition costs and cheaper permitting. Then the data center operators would pay 30% of this lower cost. By buying solar and storage at this now much-reduced price, households would get electricity at about a 30% discount off utility rates, while the tech companies would be able to buy capacity at a cost comparable to that of building a new gas plant.

You’ll notice the proposal assumes tech companies pay only a portion of the costs for the residential upgrades, so residents still face upfront costs – 50% of the cost of heat pumps, 70% of a hopefully-lowered price for solar and batteries. Rewiring America calculates that residents will come out ahead under all scenarios, while the data centers will pay only a little more than they would otherwise have to pay, buying capacity they might not otherwise be able to get.

Because Virginia has so many more data centers than anywhere else on earth, Rewiring America calculates that all of these investments would meet only 25% of our projected new data center demand. Other states could do much better, fully meeting projected new demand across most of the country and even exceeding it in about half the states. Virginia would presumably stand to benefit from surplus capacity in other PJM states.

Obviously, these calculations describe a best-case scenario, and I have my doubts about whether the uptake would be anywhere near what they believe is possible. Still, even capturing just a portion of the efficiency potential Rewiring America believes is there would relieve some of the pressure on the grid.

But is there really that much low-hanging efficiency fruit in Virginia? If the NREL data that the researchers use is correct, more than 300,000 single family homes in Virginia have electric furnaces. Yet electric furnaces are notoriously inefficient and expensive to operate, and heat pumps have been around for decades. Our utilities have been running energy efficiency programs for years that are supposed to help residents save energy. Can there really be that many single-family homes that have not converted to heat pumps yet?

I consulted Andrew Grigsby, a home energy efficiency expert who is currently the energy services director at Viridiant, a nonprofit focused on sustainable buildings. Grigsby shared my doubts about the accuracy of NREL’s estimate of the number of homes with electric resistance heat, saying it was at odds with his experience. He also felt that an efficiency program would save more energy at less cost by targeting improvements to the needs of each home, instead of supplying a blanket solution.

But he also refuted my assumption that most of the low-hanging fruit should have been picked by now. “Virginia has 100,000 homes (at least) where three hours work and $50 in materials would reduce heating/cooling costs by 25% — via fixing the obvious, massive duct leakage,” he said in an email.

This doesn’t mean Rewiring America’s approach wouldn’t save energy; rather, it supports the conclusion that there is a massive opportunity for energy efficiency savings that Virginia hasn’t fully tapped into.

Legislators have tried. The VCEA set efficiency targets for Dominion and APCo, and the SCC followed up with further targets. APCo has consistently met its goals, Dominion has not. A review of Dominion’s sad little list of programs available to homeowners suggests that the problem is a lack of ambition, not a lack of opportunity.

An aggressive, third-party operated efficiency program would complement the Virtual Power Plant (VPP) pilot program that Dominion is developing in accordance with legislation passed in the 2025 session. The VPP’s goal is to shift some consumption to off-peak times, while the Rewiring America proposal would reduce overall consumption.

Both seek to achieve time-shifting through incentivizing residents to invest in home batteries, their only area of overlap. But whereas the VPP legislation set only 15 MW as its baseline target for home batteries, the Rewiring America proposal could incentivize much more, along with the solar systems to charge them.

The problem remains how to get tech companies to pay for it. My contact at Rewiring America, senior director of communications Alex Amend, pointed me to approaches being undertaken in other states. Minnesota legislation requires data centers to contribute between $2 million and $5 million annually toward energy conservation programs that benefit low-income households. Georgia Power is expected to file a large load tariff that, says Amend, includes pathways for off-site, behind-the-meter solutions.

Here in Virginia, though, both APCo and Dominion, as well as some co-ops, have already submitted large-load tariff proposals to the SCC as part of their rate cases. None of the proposals include incentives for demand reductions anywhere, much less the residential sector. Indeed, given Dominion’s track record on efficiency, the SCC would have to take the initiative to meld a large load tariff for data centers with the VPP program and aggressive home efficiency investments.

The SCC has announced plans to hold a technical conference on Dec. 12 to examine data center load flexibility. Rewiring America hopes to participate to lay out its proposal in more detail.

Then maybe we’ll see if the cats will pay for the dog park.

This article was originally published in the Virginia Mercury on November 10, 2025.