Wednesday marked crossover at the General Assembly, the day on which bills that have passed the House move to the Senate, and vice-versa. Any legislation that didn’t clear its chamber by now is dead for the year.

That should mean that by this point we can predict which major policy initiatives are likely to become law. That looks to be true of the energy bills I wrote about last week, where the House and Senate are pretty well aligned. With data center legislation, though, the situation remains more fluid.

Legislators put in scores of bills addressing various problems the data center boom has brought for communities, water supplies, the electricity grid and consumers, and even the hard-core, pro-development leadership agrees on the need for fixes. They just don’t agree on what those are.

In recent days, House and Senate leaders have coalesced around a limited number of preferred solutions. The catch is, the House solutions are mostly different from the Senate solutions. The second half of the session could be lively.

One thing House and Senate leaders from both parties agree on is that they want the data center boom to continue, and they aren’t taking guff on this point from the rank-and-file, not to mention angry community members. New delegates, elected on promises to rein in Big Tech, are learning how little their campaign promises matter when the subcommittee hearing their bill has received instructions from leadership to send it to a quick death.

That said, leaders also agree on some other points. One is so obvious that you wouldn’t think it would need stating, much less legislating: If all the tweaks the General Assembly makes to the supply side of the equation don’t result in enough new power availability fast enough, the data centers must wait to connect.

Utilities, however, have raised the concern that their “duty to serve” all comers may tie their hands. As a result, last fall the Commission on Electric Utility Regulation (CEUR) crafted legislation that was introduced this year as HB 1151, from Del. Rodney Willett, D-Henrico, and SB 423, from Sen. Russet Perry, D-Loudoun. The legislation allows a utility to delay service to a customer whose demand exceeds 90 MW if needed for system reliability or to avoid exceeding existing generation or transmission capability.

Remarkably, the House bill (but not the Senate bill) has a delayed effective date of July 1, 2027, indicating that House leaders are reluctant to slow the data center buildout even to protect the reliability of the electricity supply. The leadership split is even more evident in the treatment of a stronger version of the CEUR legislation, discussed in the energy section below, that would require sign-off from the State Corporation Commission before a data center of over 90 MW can connect. While the Senate bill has passed, the House bill was killed in committee.

Another point of divergence within the legislature is on what to do about Virginia’s tax exemption for data centers, now approaching $2 billion per year. On his way out the door, Gov. Glenn Youngkin left a budget with a provision (Item 4-14 #18) extending the data center tax incentive from 2035 to 2050 with no strings attached.

Conversely, Sen. Danica Roem, D-Manassas, submitted a budget amendment canceling the incentive altogether. Roem’s approach might be the more fiscally prudent, but there’s no indication it has support of General Assembly leaders or Gov. Abigail Spanberger.

Occupying the middle ground is legislation that extracts concessions from companies that take advantage of the subsidy, as well as measures addressing the collateral effects on residents and the environment levied by so many data centers using so many resources. These will all be improvements – if they survive the coming weeks.

You will notice that many of the bills discussed below apply only to the largest data centers, “hyperacalers” that draw as much power as a city. Data centers of this size were virtually unknown a decade ago, when 30 MW was considered large. The data centers in Northern Virginia that first worried planners with their energy demand — and angered community members with their noise and pollution — averaged about 20 MW. Today, data center proposals of 1,000 MW or more are not unheard of. Tech companies are planning as if the world had unlimited resources to serve them, while the rest of us live in a world of natural resource constraints. If Speaker Don Scott and other House leaders remain resistant to controls on the spread of these grid-deforming behemoths, Virginia will face increasing crises of power availability and reliability, water shortages and escalating utility rates. Is that really what they want?

The energy problem

Using the tax exemption as leverage is the idea behind HB 897 from Del. Rip Sullivan, D-Fairfax, and SB 465 from Sen. Creigh Deeds, D-Charlottesville. Both bills condition the tax exemption on data centers achieving high energy efficiency standards, purchasing carbon-free energy, and decreasing the use of their highly-polluting diesel backup generators. Both legislators have put in similar bills for three years in a row, and last year Deeds even tried to use the budget process to get the provisions into law.

Sullivan has been working his bill hard, making concessions where he feels he needs to in hopes of getting the legislation across the line. In the form that passed the House, data centers that want the tax exemption would have to meet one of several options to demonstrate a high measure of energy efficiency.

In addition, they would have to use zero-carbon electricity for a percentage of their demand, reflecting Virginia’s renewable portfolio standard (RPS) but accelerated by 10 years. That means data centers in Dominion territory would have to reach 100% zero carbon energy by 2035; for those in Appalachian Power territory, that date would be 2040. Data centers located in the territory of a rural electric cooperative, where the RPS doesn’t apply, would have to meet the RPS requirements of Appalachian Power, again accelerated by 10 years.

Thirdly, data centers would not be allowed to use co-located fossil fuel generation (like onsite gas plants) other than for backup, and would have to shift away from using the highly polluting “Tier II” diesel generators that are the current industry standard. The requirements for this shift differ for existing and new data centers, but no backup generators could be used for non-emergency purposes.

A final addition to the bill requires utilities to petition the SCC for approval of a program enabling large energy customers to participate in “demand response or other voluntary programs” using the customer’s on-site solar, wind, energy storage, or zero-carbon electricity generating resources. Such a program would compensate the data center for investments in clean energy while helping the utility meet demand.

Encouraging as these provisions are, Sullivan told me that even though his bill has passed the House, negotiations on its final language will continue as it makes its way through the Senate.

Meanwhile, over in the Senate, Deeds’ bill never changed after he introduced it. The legislation provided that data centers that want to enjoy the tax exemption must use 90% renewable energy by 2028, meet high energy efficiency standards based on a single metric (power usage efficiency) and not use diesel fuel for onsite generation after 2031. The bill never got a hearing in committee, however, suggesting that Senate leadership intended its quiet death all along.

Senate leadership was apparently more pleased with SB 619 from Sen. Kannan Srinivasan, D-Loudoun, which requires SCC sign-off before a data center can become operational. Under the bill, the SCC would issue the certificate only if it finds that a high load facility (over 90 MW) will have no material adverse effect on the rates paid by other customers, and won’t affect reliability or the utility’s ability to meet environmental laws and regulations. This last condition can be met by showing that the data center will take measures “reasonably designed to offset its contribution to the utility’s peak demand,” such as using energy storage or zero-carbon energy sources.

From a ratepayer’s point of view, this is the most protective bill still alive at the General Assembly. Yet, while Srinivasan’s bill passed the Senate, a similar House bill was killed in committee, making SB 619’s fate in the House uncertain.

Other bills that apparently have the blessing of leadership in both chambers are HB 284 from Del. Michael Feggans, D-Virginia Beach, and SB 371 from Jeremy McPike, D-Prince William. The legislation directs the SCC and utilities (including the cooperatives) to develop voluntary demand flexibility programs for high energy demand customers to reduce their demand at peak times or other times the grid is strained. They can do it in one of two ways: by reducing demand at peak times themselves, or by securing peak load reductions from other customers (like residents).

Specifically mentioned in the legislation is the kind of program proposed by Electrify America last fall, in which hyperscalers could buy heat pumps, solar panels and batteries for residents as a way to free up capacity on the grid, making room for their data centers and speeding up interconnection timelines.

SB 267 from Sen. Schuyler VanValkenburg, D-Henrico, shares a theme with Feggans’ and McPike’s legislation. It directs the SCC to look for cost-savings within the existing electricity system, including potential voluntary pathways by which large customers could finance alternatives as a condition of interconnection.

HB 323 from Sullivan instructs the Department of Energy to set up a work group to study ways to use the waste heat from data centers.

SB 43 from Roem directs the Department of Energy to conduct a study and make recommendations for cost-effective demand response programs that can reduce consumption during grid emergencies while not increasing air pollution from fossil fuel generators.

SB 554 from Srinivasan allows (not requires) a locality to consider the adverse impacts on the grid of any high-energy user, together with the impacts of the new infrastructure that would be needed.

HB 591 from Del. Shelly Simonds, D-Newport News, is sort of a “best practices” policy statement for data centers, favoring their “responsible operation.” However, the bill imposes no actual requirements.

Finally, one bill addresses one multi-billion-dollar question everyone is asking and no one knows the answer to: Is the data center onslaught really as huge as it appears? HB 892 from Del. Irene Shin, D-Fairfax, directs the SCC to investigate utilities’ load forecasts (as well as compliance with the RPS).

But no one seems to be asking the question that’s top of mind for me: Why is it that with access to all the data and information in the world and the astounding computational power of artificial intelligence, Big Tech can’t solve its own energy (and water) problems?

The diesel generator problem

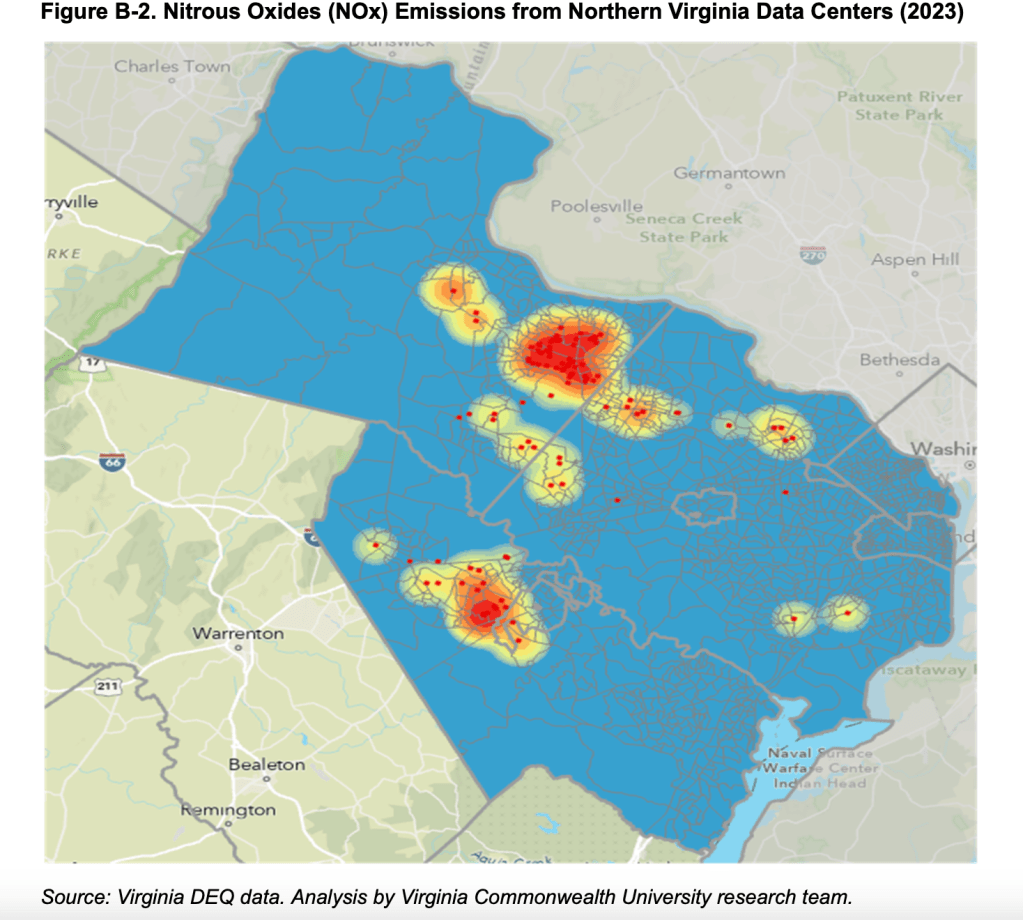

Pollution from diesel back-up generators at data centers is an emerging air quality threat in Northern Virginia. As I wrote a few weeks ago, researchers from Virginia Commonwealth University found that diesel pollution from Northern Virginia data centers is already impacting surrounding neighborhoods. Their report, now final, also warns that the total emissions allowed by data center permits in the region is a far greater threat.

Two more things happened this winter. First, after earning blistering criticism from residents for allowing data centers to run their dirty “Tier II” emergency generators in non-emergency situations, Virginia’s Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) quietly moved to require cleaner generators for all uses, as a Dec. 29 memo shows.

While that is good news, DEQ does not propose to restrict those cleaner “Tier IV” generators to emergency use. The risk is growing that data centers might run diesel generators for long periods to support the grid, causing air quality problems.

In fact, exactly that possibility arose in late January, when grid operator PJM received authorization from the U.S. Department of Energy to order Northern Virginia data centers to run their emergency generators in support of the grid over a few days of extreme cold.

That makes DEQ’s move to require Tier IV-equivalent generators seem both prescient and insufficient.

Of the House bills still alive, the strongest language on diesel generators is in Sullivan’s HB 897, discussed above. Since that bill only affects data centers that wish to take Virginia’s tax exemption, it is in a sense voluntary, though it’s hard to imagine a data center foregoing so much free money. The bill is also prospective, with a time lag and a phased-in approach.

As Virginia Mercury reporter Shannon Hecht wrote this week, other bills addressing generators have not fared well.

HB507 from Del. John McAuliff, D-Fauquier, started out as an aggressive bill to reduce the use of diesel generators by prohibiting them from being used for non-emergency purposes, requiring the ones that are used to be Tier IV or the equivalent, and making data centers use energy storage as their primary backup power source. The bill also called for air monitoring. Strong-arming from the House leadership has led to a substitute that does nothing more than codify DEQ’s new guidance requiring new generators to achieve Tier IV controls.

HB 1502, from Del. Elizabeth Guzman, D-Prince William, directs DEQ to perform a statewide study of pollution from standby generators used by any kind of commercial facility, identifying the type and amounts of pollutants. It also started out as a stronger bill, but a study seems to be as far as House leadership is willing to go to address air pollution concerns.

Only one surviving Senate bill addresses diesel generators, and it is remarkably weak. Roem’s SB 336 began as a bill to reverse DEQ guidance expanding the definition of an “emergency” for the purpose of allowing a data center to use its uncontrolled Tier II diesel backup generators.

Now the bill has morphed into a directive to the SCC to merely evaluate the impact of requiring data centers to limit the use of Tier II generators and of requiring that they replace 20% of their Tier II generators each year to bring them up to Tier IV standards. The SCC will also look at what other states are doing, and how diesel generators are regulated for other users within Virginia.

The water problem

HB 496 from Guzman originally required data center operators to submit expected water use estimates to localities for both special exception and by-right permits, including average daily use, maximum daily use, and total maximum annual use. The applicant would not be allowed to use nondisclosure or confidentiality agreements to keep the information secret.

It was first killed in committee, but then brought back from the dead and amended with language drafted by data center lobbyists. In its latest iteration, it allows localities, as part of a zoning ordinance (thus excluding by-right development), to require data centers to submit annual (but not daily) water consumption estimates, and to consider water consumption from public resources in its rezoning and special use permit decisions. The information would be publicly accessible in the applications.

In the Senate, Srinivasan’s SB 553 requires water providers to report on water volumes provided to data centers they serve.

The cost-shift problem

SB 253, from Sen. Louise Lucas, D- Portsmouth, started out as an initiative to increase the amount of funds Dominion and APCo must spend on low-income energy assistance and weatherization. Along the way it has become a vehicle for a plan to make data centers pay more of the energy and distribution costs Dominion incurs.

However, Lucas also includes a giveaway to Dominion for its program putting lines underground, which will increase residential bills over the next 20 years. Lucas has added the name Fair and Affordable Electric Rates and Reliability Act to her bill, and says it will save the average resident $5.50 per month.

Sadly, even if Lucas’s bill passes the House, the average resident is not likely to notice this savings among the rate increases Dominion has secured in the past year. In addition to charging ratepayers for undergrounding lines, the SCC recently granted Dominion’s request to raise rates and collect more in profit. On top of that, the soaring cost of fossil gas led the SCC to approve a higher “fuel factor” for Dominion customers, calculated to cost the average resident almost $9 per month.

Still, the fact that the data centers opposed Lucas’ bill in committee indicates that the industry’s perfect record for extracting subsidies from Virginia taxpayers and ratepayers year after year may have suffered a tiny injury, perhaps even on the order of a pinkie sprain. But the session isn’t over yet.

A different cost allocation bill also made its way through the Senate. Perry’s SB 339 requires the SCC to initiate proceedings to determine whether non-data center customers of Dominion and APCo are subsidizing data center customers under the current cost allocation for transmission, distribution and generation projects. The SCC is empowered to change the cost allocation formula as it deems appropriate. However, the companion House bill from Del. Michelle Maldondo, D-Manassas, was tabled (killed) in a subcommittee, making the prospects for Perry’s bill uncertain in the House.

The House also killed a blunter instrument from McAuliff (HB 503), which prohibited a utility from recovering costs for serving data centers over 100 MW except from data centers.

The transmission problem

Local governments issue permits for data centers to be built, but it’s the utility that has to build distribution lines and substations to connect data centers to the grid. Enough data centers drawing enough power can even trigger the need for new interstate high-voltage transmission lines such as one Dominion Energy plans to build to bring more power from the Ohio River valley to Northern Virginia data centers.

Yet residents don’t want transmission lines running through their neighborhoods or parks, and they don’t want to pay for lines that are needed only for data centers.

Under Virginia law, residents have little choice in either matter. Utilities can use eminent domain to seize land from unwilling sellers for new lines, and current cost allocation rules make residents shoulder more than 50% of the cost of Dominion’s transmission projects.

The Perry and Lucas bills discussed above address the cost allocation problem for transmission as well as generation. But having decided to encourage an unlimited number of new data centers into the state, legislators can’t very well stop new transmission lines. (And, I feel compelled to add, Dominion’s choice to build massive interstate transmission lines carrying fossil-fuel power is the natural result of Virginia counties rejecting solar projects that would have been located near existing distribution lines.)

A couple of House bills do try to limit the pain. HB 889 from Shin establishes an order of preference for transmission line siting, with existing utility corridors in first place, then highway corridors, and new corridors last.

HB 1491 from J.J. Singh, D-Loudoun, directs the SCC not to approve a new transmission line if it would be close to residences or schools unless no other feasible alternative exists, or if it would conflict with open space and environmental protection.

SB 827 from Srinivasan and HB 1487 from Singh is narrowly targeted but interesting as a possible model for putting lines underground. Burying wires is much more expensive than stringing them on poles, but it is also more popular with communities. The legislation authorizes the SCC to approve up to four applications for undergrounding of high-voltage lines, if the local government foots the bill for half the added cost.

Of the four projects, one is specified in the bill with a description that fits the 8.3 mile Golden-Mars transmission project serving data centers in Loudoun County.

The there-goes-the-neighborhood problem

Only one initiative addresses the constant, loud hum from data centers’ air conditioning systems that drives the neighbors batty.

HB153 from Del. Josh Thomas, D-Prince William, calls for a locality to require a high energy use facility (HEUF, defined as 100 MW or more) to perform a site assessment examining its sound profile as part of any rezoning, special exception or special use permit.

The locality may (not must) also require the site assessment to include the HEUF’s effect on other resources at the site or contiguous to it, including ground and surface water, forest and parks. The locality must also get from the electric utility a form describing substations and transmission required to serve the facility.

However, none of these requirements apply to an already-approved data center that seeks to expand its operations by less than an additional 100 MW, meaning an existing small facility could be turned into an enormous one without the additional review.

In the Senate, a companion bill was rolled into Roem’s SB 94, which was a very different bill until, late in the process, it was amended to look like HB 153 – with one difference. Roem’s bill adds a provision that beginning July 1, 2027, if a locality has adopted a zoning ordinance, data centers can only be placed on land zoned industrial unless the land is part of a larger development and will share the energy connection of the adjacent parcel.

This legislation won’t satisfy community members who today feel under siege from the onslaught of data center development. But as General Assembly leaders are making clear, the onslaught will continue.

A version of this article was originally published on February 20, 2026 in the Virginia Mercury.

Update, February 23: Clearly I’m a lousy prognosticator. After dismissing the possibility of the General Assembly rolling back the tax exemption for data centers, I now have to report that the budget the Senate adopted proposes to do just that, ending the exemption in 2027. The House budget does no such thing, however, so get your popcorn ready to watch the action. Sullivan’s HB897, which relies on the tax exemption as the carrot to achieve its goals, may now be in jeopardy in the Senate. If the House prevails in keeping the exemption intact, it could achieve Sullivan’s purpose by putting the conditions into the budget. Or it could do something else entirely. . .