Virginia’s ever-growing fleet of data centers will take the spotlight when the General Assembly reconvenes this week. Along with bills addressing issues like energy use and siting, legislators will need to address a problem that received little attention in previous years: the diesel generators that provide backup power in emergencies.

In Northern Virginia, where most data centers are concentrated, millions of people are exposed to air pollution from thousands of massive diesel generators. Air toxins permeate the surrounding area every time these generators are run for routine testing and maintenance, with greater levels of pollution when they all kick on at once in a grid emergency. As more data centers go up in suburban neighborhoods and close to schools, residents fear that their health, and that of their children, is being sacrificed to Big Tech’s AI ambitions.

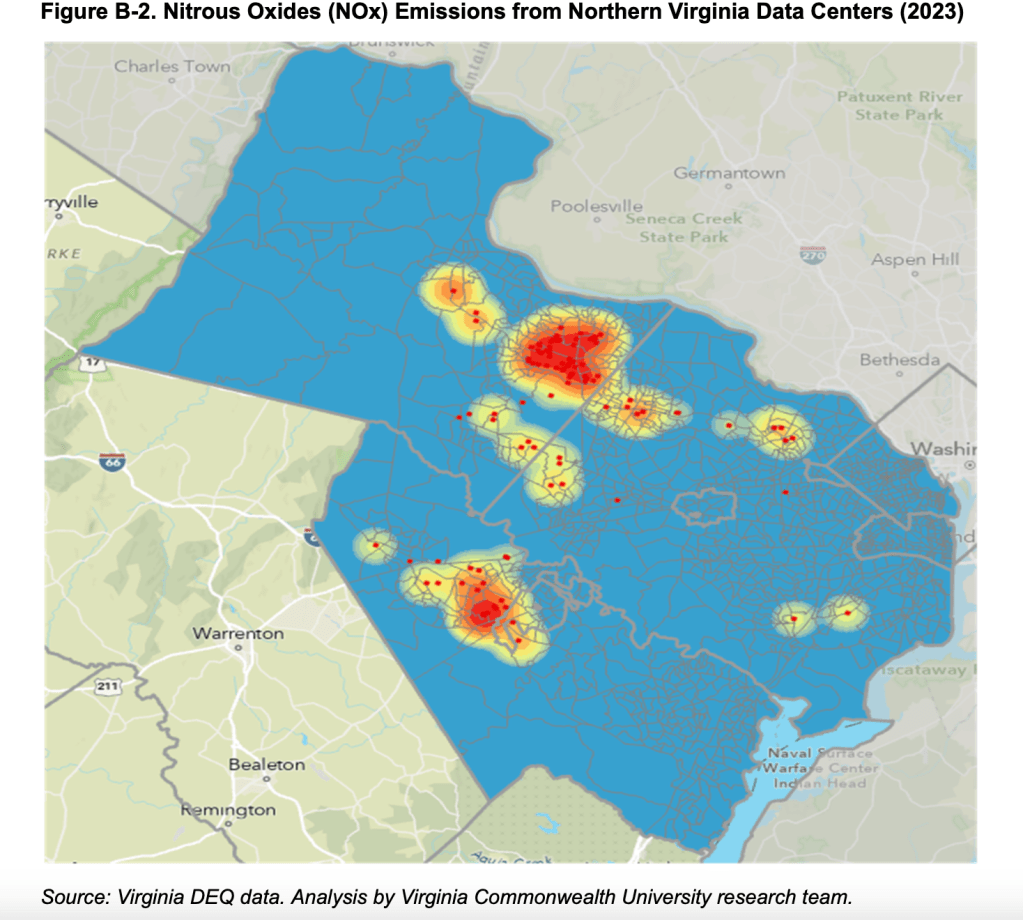

Ongoing research led by Dr. Damian Pitt at Virginia Commonwealth University, using data from the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), shows pollution from data centers currently makes up a very small but growing percentage of the region’s most harmful air emissions, including CO, NOx and PM2.5. (In pollution, the automobile is still king.) Already the appendix to the report, using 2023 data, shows significant impacts to neighborhoods around data centers in Loudoun and Prince William counties, exceeding emissions from other high-pollution facilities in the region.

(Map courtesy Damian Pitt/Virginia Commonwealth University research team)

But as the research team noted, the total allowable emissions under DEQ permits is far greater, and this also keeps growing with construction of each new data center.

And those are annual limits, which could be met with very high emissions on a limited number of days. It’s not hard to imagine the health crisis that might accompany a grid emergency causing all of the area’s generators to fire up at once on a hot summer day, perhaps when smoke from wildfires is already pushing air quality into the hazard zone.

Yet the problem grows with every new data center that’s built, each one requiring backup power on site. In Virginia, diesel is the fuel of choice, most of it burned in so-called Tier II emergency generators with no pollution controls.

In the past year, large operators have started installing Tier IV generators in addition to Tier II generators. The Tier IV have some pollution controls and are not restricted to emergency use. They are subject to the same annual emissions limits, but as long as they stay under the permitted level there is no limit on how much they can run.

The new trend suggests that operators who install these non-emergency generators either think their Tier II generators may be used so much in the future that it will put the data center at risk of exceeding the permit’s annual air pollution limits – which would be bad – or they intend to use the Tier IV generators outside of emergency situations – which might be worse.

Either way, it appears operators expect to burn a lot more diesel fuel in coming years. One Amazon permit I reviewed contemplates a single data center using up to ten million gallons of diesel fuel annually for 173 generators. All that diesel fuel is delivered by diesel trucks, which adds to the region’s pollution but isn’t limited by the permits.

Why so much? DEQ guidance from January 2025 indicates that data centers have two to three levels of redundancy in their generator capacity – that is, backups for the backups, so operators never have to fear losing power if some of the generators won’t start. As a result, there is more generator capacity than data center load. Together, Northern Virginia’s 4,000-plus diesel generators add up to over 11 gigawatts of energy capacity – exceeding Dominion Energy’s entire natural gas fleet, and enough to power millions of homes.

But of course, they don’t power millions of homes. They are used only for data centers, and when all goes well, they aren’t used at all. These thousands of generators just sit around doing nothing.

Apparently, this is the cheapest possible way to ensure data centers never lose power, but it’s hard to believe they can’t do better. If there is redundancy anyway, data centers ought to be using batteries or other storage as their first line of defense in an outage, reserving Tier IV for second-line backup and eliminating Tier II generators altogether. Typical lithium-ion batteries provide four hours of electricity, enough to cover most backup needs and still leaving room to help the grid meet peaks in demand.

A (very) few operators are in fact doing this, but unless Virginia acts to require it, Big Tech has little incentive to prioritize clean backup power. The use of diesel generators offloads the true cost of backup power onto residents in the region, who pay in the form of worse health outcomes and a lower quality of life. Evidently that suits the tech companies just fine.

While residents demand an end to the pollution, Virginia’s government has been going in exactly the opposite direction. This fall, DEQ amended a guidance document to allow Tier II generators to run more often. DEQ achieved this by changing the definition of “emergency” to include planned power outages, such as might occur when a utility schedules work on a substation that supplies electricity to a data center.

DEQ cut some legally-questionable corners to get this change finalized two weeks before the end of Glenn Youngkin’s term as governor. When word got out, more than 500 people submitted comments online and by email, overwhelmingly opposed to easing generator restrictions. Only a small handful of commenters supported the change, mainly the data centers themselves and a couple of their chamber of commerce allies.

DEQ didn’t respond to ordinary residents, but the letter it mailed to what seems to have been a select few commenters was unrepentant. DEQ did not even acknowledge the suggestions that it require batteries instead of allowing the increased use of the dirtiest diesel generators.

Pressure will now be on the General Assembly to tackle the issue. This session will likely see the reintroduction of legislation offered in 2024 and 2025 by Sen. Creigh Deeds, D-Charlottesville, and Del. Rip Sullivan, D-Fairfax, limiting or banning the use of diesel generators at data centers as part of larger bills addressing their energy use.

And this year a new Loudoun County Democrat, Del. John McAuliff, has introduced legislation requiring data centers to use storage as the first line of defense in emergencies, limiting Tier IV generators to emergency use when storage is exhausted, and removing the option of Tier II generators altogether. The bill also adds air monitoring and public notification requirements.

No doubt the data center lobby will resist these measures, as they have absolutely every initiative that would require them to shoulder the cost of their presence in Virginia. Their allies in the General Assembly will fret that requiring Amazon to prioritize cleaner alternatives to diesel generators might raise costs incrementally for a multinational company and its billionaire chief.

That feels increasingly out of touch. In November a Virginia government report calculated that the data center industry received more than $2.7 billion in incentives over the past decade, thanks to Virginia taxpayers.

It shouldn’t be any surprise that now the taxpayers would like a little consideration in return.

This article was originally published on January 14, 2026 in the Virginia Mercury.

Update: On December 29, 2025, DEQ quietly released a “revision” to its guidance memo on permit-writing procedures for diesel generators. For permits received after July 1, 2026, the revision adopts a “presumptive Best Available Control Technology” (BACT) for both emergency and non-emergency generators at data centers that will now be based on Tier IV generators or the equivalent. As I understand it, this means new data centers will be expected to have pollution controls on their emergency generators — a welcome improvement! — unless they are able to persuade DEQ otherwise.