A Solar Foundation analysis showed Virginia could create 50,000 new jobs by committing to build enough solar to meet 10% of energy demand. Photo credit: Dennis Schroeder, NREL

If there is an energy issue that Republicans and Democrats can agree on, it is support for solar energy. It’s homegrown and clean, it provides local jobs, it lowers our carbon footprint, and it brings important national security and emergency preparedness benefits. Dominion Energy Virginia even says it’s now the cheapest option for new electric generation.

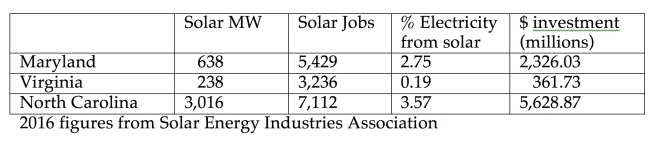

Yet currently Virginia lags far behind Maryland and North Carolina in total solar capacity installed, as well as in solar jobs and the percentage of electricity provided by solar. And at the rate we’re going, we won’t catch up. Dominion’s current Integrated Resource Plan calls for it to build just 240 megawatts (MW) per year for its ratepayers. How can we come from behind and score big?

First, our leaders have to set a serious goal. Virginia could create more than 50,000 new jobs by building enough solar to meet just 10 percent of our electricity demand by 2023. That requires a total of 15,000 MW of solar. Legislators should declare 15,000 MW of solar in the public interest, including solar from distributed resources like rooftop solar.

The General Assembly should consider a utility mandate as well. Our weak, voluntary Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) will never be met with wind and solar, and making it mandatory wouldn’t change that. (To understand why, read section 4 of my 2017 guide to Virginia wind and solar policy, here.) Getting solar into the RPS would require 1) making it mandatory; 2) increasing the targets to meaningful levels (including removing the nuclear loophole); 3) including mandatory minimums for solar and wind so they don’t have to compete with cheap renewable energy certificates (RECs) from out-of-state hydroelectric dams; and 4) providing a way for utilities to count the output of customer-owned solar facilities in the total, possibly through a REC purchase program to be set up by the State Corporation Commission.

The other way to frame a utility mandate would be to ignore the RPS and just require each utility to build (or buy the output of) its share of 15,000 MW of solar. Allowing utilities to count privately-owned, customer-sited solar towards the total would make it easier to achieve, and give utilities a reason to embrace customer investments in solar.

Second, the General Assembly has to remove existing barriers to distributed solar. Customers have shown an eagerness to invest private dollars in solar; the government and utilities should get out of the way. That means tackling several existing barriers:

- Standby charges on residential solar facilities between 10 and 20 kilowatts (kW) should be removed. Larger home systems are growing in popularity to enable charging electric vehicles with solar. That’s a good thing, not something to be punished with a tax.

- The 1% cap on the amount of electricity that can be supplied by net-metered systems should be repealed.

- Currently customers cannot install a facility that is larger than needed to serve their previous year’s demand; the limitation should be removed or raised to 125% of demand to accommodate businesses with expansion plans and homeowners who plan to buy electric vehicles.

- Customers should be allowed to band together to own and operate solar arrays in their communities to meet their electricity requirements. This kind of true community solar (as distinguished from the utility-controlled programs enabled in legislation last year) gives individuals and businesses a way to invest in solar even if they don’t have sunny roofs, and to achieve economies of scale. If community solar is too radical a concept for some (it certainly provokes utility opposition), a more limited approach would allow condominiums to install a solar facility to serve members.

- Local governments should be allowed to use what is known as municipal net metering, in which the output of a solar array on government property such as a closed landfill could serve nearby government buildings.

- Third-party power purchase agreements (PPAs) offer a no-money-down approach to solar and have tax advantages that are especially valuable for universities, schools, local governments and non-profits. But while provisions of the Virginia Code clearly contemplate customers using PPAs, Virginia utilities perversely maintain they aren’t legal except under tightly-limited “pilot programs” hammered out in legislation enacted in recent years. The limitations are holding back private investment in solar; the General Assembly should pass legislation expressly legalizing solar third-party PPAs for all customers.

Third, the Commonwealth should provide money to help local governments install solar on municipal facilities. Installing solar on government buildings, schools, libraries and recreation centers lowers energy costs for local government and saves money for taxpayers while creating jobs for local workers and putting dollars into the local economy. That makes it a great investment for the state, while from the taxpayer’s standpoint, it’s a wash.

If the state needs to prioritize among eager localities, I recommend starting with the Coalfields region. The General Assembly rightly discontinued its handouts to coal companies in that region, which were costing taxpayers more than $20 million annually. Investing that kind of money into solar would help both the cash-strapped county governments in the area and develop solar as a clean industry to replace lost coal jobs.

Coupled with the ability to use third-party PPA financing, a state grant of, say, 30% of the cost of a solar facility (either immediately or paid out over several years) would drive significant new investment in solar.

Fourth, a tax credit for renewable energy property would drive installations statewide. One reason North Carolina got the jump on Virginia in solar was it had a robust tax credit (as well as a solar carve-out to its RPS). One bill has already been introduced for Virginia’s 2018 General Assembly session offering a 35% tax credit for renewable energy property, including solar, up to $15,000. (The bill is HB 54.)

Fifth, Virginia should enable microgrids. Unlike some other East Coast states, we’ve been lucky with recent hurricanes. The unlucky states have learned a terrible lesson about the vulnerability of the grid. They are now promoting microgrids as one way to keep the lights on for critical facilities and emergency shelters when the larger grid goes down. A microgrid combines energy sources and battery storage to enable certain buildings to “island” themselves and keep the power on. Solar is a valuable component of a microgrid because it doesn’t rely on fuel supplies that can be lost or suffer interruptions.

The General Assembly should authorize a pilot program for utilities, local governments and the private sector to collaborate on building solar microgrids with on-site batteries as a way to enhance community preparedness, provide power to buildings like schools that also serve as emergency shelters, and provide grid services to the utilities.

One way or another, solar energy is going to play an increasingly large role in our energy future. The technology is ready and the economics are right. The only question is whether Virginia leaders are ready to make the most of it in the coming year.

Ivy, as a solar installer there are some points I would like to bring up. A mandatory RPS would be essential to solar growth. The idea of the utility using homeowner or other installs to meet this would be essential. The Dominion Power solar buyback program is an excellent example, while very small and currently used up, this should be substantially expanded.

I constantly run into our local utility challenging us on the size of our systems based upon last year usage. Our customer are moving to a previous second home or adding EV chargers.

To speak in favor of the utilities , they should be allowed a charge on people adding solar as the utility is required to maintain and service the grid. The concept of “free riders” comes into play with the solar installation paying nothing to the utility company.

As a solar installer:

Dominion’s solar buyback program produces taxable (1099) income for the consumer, in most cases bringing them below the retail cost of a kWh. It was a farce.

Secondly, there are no “free riders” in net metering. They constantly produce cheap power at peak load times when utilities are commonly paying higher than the retail price for power, likely offsetting whatever free ride you think they’re getting from the grid.

Ivy, we have a public hearing on a proposed solar farm here in King George; we exchanged some emails about that a couple of weeks ago. I want to testify in support. One of the things I’d like to mention is that there are X number of solar farms in the state and that they’re doing fine. Do you have access to a list of solar farms? Thnx!

Should have said we have a public hearing “coming up”. It’s on the 19th.

Virginia has the oldest school buildings in the country, Richmond has the oldest school buildings in the state.

This past election, the Sierra Club Falls of the James endorsed and helped pass a grassroots referendum to require school modernization planning. http://www.PutSchoolsFirst.org. It’s already forcing much needed conversation in Richmond.

Will local environmental and faith-based groups join the Sierra Club Falls of the James in calling for energy conservation, green building, and solar roofs to be part of Richmond school modernization?

We know that Dominion and the Richmond Children’s Museum are partnering to put small, ‘experimental’ solar on a few school roofs, but citizens should be demanding that Richmond install large,’working’ solar arrays on public schools (and elsewhere). Other Virginia localities are in the process of doing so now, often at their students’ urging. Below is a link to the Arlington Public Schools’ Solar PPA RFP. Why not RVA?

Click to access RFP-01FY18-Appendix-I.pdf

The only viable way to transition our grid to clean energy is to optimize the cost using real accounting, not phony cost-shifting shell games like net-metering. Utility scale clean energy is now and always has been the cheapest way to power the grid. Most of our current billing plans (i.e. those with net-metering) hide this clear truth by shifting grid costs for residential electric service away from those with PV systems and onto other electricity customers. That’s why regulators often impose caps and restrictions on net-metering.

Homes with PV systems should be treated like any other generators or industrial user: they should pay fixed charges to access the grid based on peak input/output, and they should buy and sell electricity at near wholesale prices (i.e. adjusted to reflect dis-economies of scale).

The ultimate test of whether a billing plan is fair is to assume everyone will use it. If we all had net-zero electricity usages, there would still be a large grid maintenance cost that someone would have to pay, so it is completely obvious that net-zero usage cannot lead to a zero electric bill. Given our high residential electricity costs of 10-30 ¢/kWh (in the US), it may come as a surprise that the wholesale cost of electricity is typically only 2-4 ¢/kWh; the rest of the retail price is used to cover real grid costs that utility regulators must distribute to homeowners in some equitable fashion.

Before home PV systems, distributing grid costs based on kWh usage seemed equitable, but nowadays it is not, and regulators understand this. We in the clean energy movement need to understand it too, and must not blindly support the home PV industry, which as the most expensive way to make solar electricity, does not have the public’s best interest at heart.

Thanks for your comments, Nathan. You make the utility’s case against net metering very nicely, but I think it answers the wrong question. The right question is: given the urgent need to transition away from fossil fuels, AND to make the grid more secure and resilient, how can we incentivize both utility scale and distributed solar generation most efficiently? States that offer net metering have more distributed solar than states that don’t. Net metering is not the only way to get distributed solar, but until we are offered a better tool for the job, let’s keep the one that works.

Pingback: How Virginia localities will get to 100% renewable | Power for the People VA