Virginia’s thirteen electric cooperatives were exempted from most provisions of the 2020 Virginia Clean Economy Act, which caps carbon pollution from power plants and requires investor-owned utilities to meet renewable-energy and energy-efficiency targets. In lobbying for the VCEA exemption, cooperatives no doubt touted their claimed status as member-owned and democratically governed. In theory that means co-op members can direct their co-ops to adopt programs friendly to consumers and the environment. But events last month showed again that some of the commonwealth’s electric co-ops are not as democratic as they claim.

Summer is annual-meeting time for electric co-ops. Like all consumer cooperatives, electric co-ops are owned by their customers (called “member-owners”). Democratic control of the cooperative is one of seven “cooperative principles” that all electric cooperatives claim to adhere to. The key to genuine democratic control is board-of-director elections, which happen at each co-op’s annual meeting, where member-owners vote for board candidates.

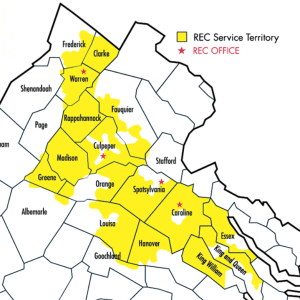

Two examples from Virginia electric co-op annual meetings last month demonstrate ways large and small in which incumbent co-op boards game the election process to help their favored board candidates. The most egregious case occurred at Rappahannock Electric Cooperative (REC), which serves rural and suburban Virginians in 22 counties. In a five-way race in REC’s August board election there was a clear winner among co-op member-owners who selected a candidate. Hanover County businessman Roddy Mitchell got more than twice as many member-owner votes as any of the four other candidates. You might call that a landslide win.

But through REC’s needlessly arcane and confusing proxy-voting process, REC’s board was able to allocate some 6,000 additional votes to the board-favored candidate, thereby swinging the election win to him. That board-favored candidate came in fourth out of five when looking at votes that member-owners cast for candidates.

When a board controls 40 to 60 percent or more of all votes, as REC’s board generally does, the board effectively controls the election outcome and “democracy” is an empty label.

REC’s board controls huge numbers of votes each year because proxy ballots left blank are deemed by REC’s board as a delegation of the member-owner’s vote to the incumbent board to decide whom to cast them for. Moreover, REC offers those who send in a proxy, even a blank one, a chance to win cash prizes. That encourages member-owners to submit blank proxies, even if they have no interest in the election or makeup of the board. REC election tally forms going back over a decade show that every year REC’s incumbent board controls enough proxies to control election outcomes. For at least the past twelve years no candidate has won a race without getting the board-controlled votes.

So the way to win an REC board election is to please incumbent board members, not to get the most votes from member-owners. That isn’t fair and it isn’t democratic. It leads to board groupthink, insulates boards from the concerns of member-owners, and discourages well-informed, knowledgeable co-op members from running for board.

A National Rural Electric Cooperative Association governance task force report recommended against using board-controlled proxies to swing election results. But REC’s board continues to ignore that recommendation years after it was made.

Meanwhile, neighboring Shenandoah Valley Electric Cooperative’s (SVEC) board changed the co-op’s bylaws at a closed board meeting in June to help out an incumbent board member facing a strong challenge from another candidate in the August election. The board added a bylaw provision saying that in the case of a tie between an incumbent and non-incumbent candidate the incumbent would be deemed the winner of a one-year board term!

As if that isn’t bad enough, REC board chair Chris Shipe said publicly a few weeks ago that SVEC’s board is considering changing its (fair) direct election process next year to a proxy system like REC’s. If SVEC follows through on that, then its board, like REC’s, will be able to determine election outcomes. That would make SVEC’s new tie-vote bylaw unnecessary. There are no ties when incumbent board members control election outcomes.

SVEC’s board would then be fully insulated from member-owner concerns. That would greatly help incumbent board members, who recently approved major fixed-monthly-charge increases that disproportionately affect the co-op’s low-income member-owners and those who’ve invested in rooftop solar or energy efficiency.

There is currently no government oversight of Virginia electric co-op elections, and no law to ensure fair board-election procedures, prohibit abusive proxy practices, or prohibit using board-imposed bylaw changes to favor incumbents. This is important because electric cooperatives are essential service providers that operate as monopolies. Monopoly utilities seldom act in the best interest of their customers unless subjected to meaningful scrutiny, accountability, and independent oversight. Such oversight is lacking when entrenched co-op boards have ironclad control of board-election outcomes. It’s time for the General Assembly to step in and ensure basic, fair election practices to give Virginia electric cooperative member-owners a true say in the governance of the utilities they own.

Seth Heald is a retired U.S. Justice Department lawyer and has a master of science degree in energy policy and climate. He is a member-owner of Rappahannock Electric Cooperative and co-founder of Repower REC, a campaign to bring genuine democracy to Virginia’s electric co-ops. More information at RepowerREC.com.