[Note: Although this is a terrific article, it is now a bit dated. You can find the 2017 update to the Virginia Wind and Solar Policy Guide here.]

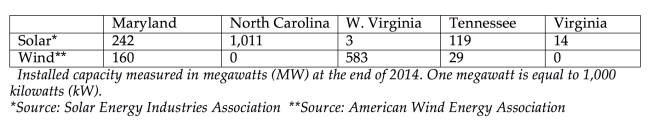

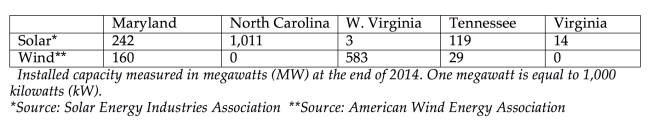

The past year has seen a lot of activity on wind and solar in the Old Dominion, and yet Virginia lags further than ever behind neighboring states in installations to date. Why? And more importantly, what can we do about it?

I’ll try to answer these questions as briefly as possible in this third annual update of Virginia renewable energy law and policy. But yes, this is a long post. If you’re the kind of person who only reads executive summaries or prefers the elevator pitch to the full Ted Talk, let me try this:

Virginia’s utility model is built on monopoly control and large, centralized generating systems, and this model does not serve 21st century needs and technologies. The free market solution is to open Virginia’s electricity market to competition and lower the barriers to customer-sited wind and solar generation.

Virginia is further than ever behind

Virginia still has no utility scale wind or solar projects and very little in the way of customer-owned and other distributed generation. The 2015 legislative session improved prospects for solar at the utility scale, but utility interest in wind remains low. Meanwhile, barriers to the rapid adoption of customer-owned generation remain firmly in place.

Virginia utilities won’t sell wind or solar to customers (and they won’t let anyone else do it either)

With one very narrow exception for commercial customers, Virginia residents can’t pick up the phone and call their utility to buy electricity generated by wind and solar farms. Worse, they can’t even buy renewable energy elsewhere.

This wasn’t supposed to happen. Section 56-577(A)(6) of the Virginia code allows utilities to offer “green power” programs, and if they don’t, customers are supposed to be able to go elsewhere for it. (See the section on third-party-owned systems for what happened when one customer tried to go elsewhere.)

Ideally, a utility would use money from voluntary green power programs to build or buy renewable energy for these customers. However, Virginia utilities have not done this, except in very tiny amounts. Instead, utilities pay brokers to buy renewable energy certificates (RECs) on behalf of the participants. Participation by consumers is voluntary. Participants sign up and agree to be billed extra on their power bills for the service. Meanwhile, they still run their homes and businesses on regular “brown” power.

In Dominion’s case, these RECs meet a recognized national standard, and some of them originate with wind turbines, but they primarily represent power produced and consumed out of state, and thus have no effect on the power mix in Virginia. For a fuller discussion of the Dominion Green Power Program, see What’s wrong with Dominion’s Green Power Program.

In the case of Appalachian Power, the RECs come from an 80 MW hydroelectric dam in West Virginia. No wind, and no solar.

The State Corporation Commission ruled that REC-based programs like these do not qualify as selling renewable energy, so under the terms of §56-577(A)(6), customers are permitted to turn to other licensed suppliers of electric energy “to purchase electric energy provided 100 percent from renewable energy.” Unfortunately (and in this English major’s opinion, wrongly), Virginia utilities claim that the statute’s words mean that not only must another licensed supplier provide 100% renewable energy, it must also supply 100% of the customer’s demand. Obviously, the owner of a wind farm or solar facility cannot do that; the customer will need to draw from the grid part of the time. Ergo, say the utilities, a customer cannot go elsewhere. Checkmate!

The SCC may rule on this interpretation some day, but there is still another problem with the statute: under its terms, customers are allowed to turn to other electric suppliers only if their own utility doesn’t offer a qualifying program. So if the SCC sides with the English majors on this one, Dominion could (and surely would) gin up a variation of its Green Power Program consisting of true renewable energy. It would still not have to offer Virginia-based wind and solar—crappy biomass and old hydro would do, so long as it was actual energy “bundled” with the RECs. Nor would it have to offer a competitive price.

Really, the statute doesn’t ask much. It’s astonishing the utilities haven’t taken steps already to close that loophole. But surely they’re ready, and that’s enough to scare off any would-be competitors.

Earlier this year Dominion seemed poised to offer customers a program to sell electricity from solar panels, which would have qualified. Notwithstanding its name, however, the “Dominion Community Solar” program is not an offer to sell electricity generated from solar energy, and seems likely to attract customers only to the extent they are deceived into believing it is something it is not.

For customers to have real energy choice in Virginia, the GA has to change the terms of §56-577(A)(6). Let people buy wind and solar from any willing seller, whether it be their utilities or the private market. Utilities will benefit by customers taking on their job of lowering Virginia’s carbon emissions. Virginians will benefit from cleaner air, new clean energy jobs, and a stronger grid.

Virginia’s Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) is a miserable sham

Many advocates focus on an RPS as a vehicle for inducing demand. In Virginia, that’s a mistake. Virginia has only a voluntary RPS, which means utilities have the option of participating but don’t have to. On the other hand, it costs them nothing to do it, because any costs they incur in meeting the goals can be charged to ratepayers. Until a few years ago, utilities even got to collect bonus money as a reward for virtue, until it became clear that there was nothing very virtuous going on.

Merely making our RPS mandatory rather than voluntary would do nothing for wind and solar in Virginia without a complete overhaul. Most important, the statute takes a kitchen-sink approach to what counts as renewable energy, so meeting it requires no new investment and no wind or solar.

The targets are also modest to a fault. Although nominally promising 15% renewables by 2025, the statute sets a 2007 baseline and contains a sleight-of-hand in the definitions section by which the target is applied only to energy not produced by nuclear plants. The combined result is an effective 2025 target of about 7%.

The RPS is as impotent in practice as it is in theory. In the case of Dominion Virginia Power, the RPS has been met largely with old hydro projects built prior to World War II, trash incinerators, and wood burning, plus a small amount of landfill gas and—a Virginia peculiarity—RECs representing R&D rather than electric generation.

There appears to be no appetite in the General Assembly for making the RPS mandatory, and even efforts to improve the voluntary goals have failed in the face of utility opposition. The utilities have offered no arguments why the goals should not be limited to new, high-value, in-state renewable projects, other than that it would cost more to meet them than to buy junk RECs.

But with the GA hostile to a mandatory RPS and too many parties with vested interests in keeping the kitchen-sink approach going, it is hard to imagine our RPS becoming transformed into a useful tool to incentivize wind and solar.

That doesn’t mean there is no role for legislatively-mandated wind and solar. But it will be easier to pass a bill with a simple, straightforward mandate for buying or building a certain number of megawatts than it would be to repair a hopelessly broken RPS.

Customer-owned generation: for most, the only game in town

Given the lack of wind or solar options from utilities, people who want renewable energy generally have to build it themselves. A federal 30% tax credit makes it cost-effective for those with cash or access to low-cost financing. The credit is available until the end of 2016 (when it falls to 10% for commercial but goes away entirely for residential).

This year the GA passed legislation enabling Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) loans for commercial customers. This should help bring low-cost financing to energy efficiency and renewable energy projects at the commercial level. That would make it the year’s most helpful piece of legislation from the standpoint of customer-owned generation.

Now that some barriers to residential PACE have been removed at the federal level, we hope the legislature will extend the law to let localities offer PACE loan programs to homeowners in the near future.

Virginia offers no cash incentives or tax credits for wind or solar. The Virginia legislature passed a bill in 2014 that would offer an incentive, initially as a tax credit and then as a grant program, but it did not receive funding, and the same bill, reintroduced in 2015, died in a subcommittee. North Carolina’s tax credit for solar is widely credited with making that state a solar leader, and it could have the same effect here. With solar panel prices continuing their breathtaking descent, utility and commercial-scale solar probably won’t need that kind of help for long, so a modest program of three-to-five years duration would suffice to catalyze the market. Residential solar would benefit from longer-lasting support.

The lack of a true RPS in Virginia means Virginia utilities generally will not buy solar renewable energy certificates (SRECs) from customers. SRECs generated here can sometimes be sold to utilities in other states (as of now only Pennsylvania) or to brokers who sell to voluntary purchasers.

Limits to net metering hamper growth

Section 56-594 of the Virginia code allows utility customers with wind and solar projects to net energy meter. System owners get credit from their utility for surplus electricity that’s fed into the grid at times of high output. That offsets the grid power they draw on when their systems are producing less than they need. Their monthly bills reflect only the net energy they draw from the grid.

If a system produces more than the customer uses in a month, the credits roll over to the next month. However, at the end of the year, the customer will be paid for any excess credits only by entering a power purchase agreement with the utility. This will likely be for a price that represents the utility’s “avoided cost” of about 4.5 cents, rather than the retail rate, which for homeowners is closer to 11 cents. Given the current cost of installing solar, this effectively stops people from installing larger systems than they can use themselves.

Legislation passed in 2015 makes it less likely that new solar owners will have any surplus. At Dominion’s insistence, the definition of “eligible customer-generator” was amended to limit system sizes to no larger than needed to meet the customers demand, based on the previous 12 months of billing history. The SCC is currently writing regulations that should address issues of new construction as well as questions arising from other new language in the law.

This limitation is crazy, no? If customers want to install more clean, renewable energy than they need and sell the surplus electricity into the grid at the wholesale power price, why would you stop them from performing this service to society? And what were Dominion lobbyists thinking, since it is clearly in their company’s interest to buy peak power at a cut-rate price? We can only speculate that the primal fear of customers with solar must be stronger even than the smell of money.

Virginia law also does not allow system owners to share the electricity with other consumers through community net metering or solar gardens. Several bills that would have permitted this were introduced in the 2013 and 2014 sessions but defeated due to utility opposition. Community net metering remains one of the solar industry’s highest priorities as a way to open the market to people who can’t own solar facilities themselves. It would also spur the market for community wind.

In August of this year, Dominion received permission from the SCC to begin a program the company is calling “Dominion Community Solar.” Reading the fine print, however, makes it apparent that participants will not actually buy solar power. They will pay a significant premium on their electric bills to fund construction of a solar installation, but the electricity generated will be sold to other people rather than credited to the participants.

Under a bill introduced by Delegate Randy Minchew (R-Leesburg) and passed in 2013, owners of Virginia farms with more than one electric meter are permitted to attribute the electricity produced by a system that serves one meter (say, on a barn) to other meters on the property (the farmhouse and other outbuildings). This is referred to as “agricultural net metering.” The law took effect July 1, 2014 for investor-owned utilities (Dominion and Appalachian Power) and July 1, 2015 for the cooperatives.

Standby charges hobble the market for larger home systems and electric cars

Dominion Power and Appalachian Power are at the forefront of a national pushback against policies like net metering that facilitate customer-owned generation.

The current system capacity limit for net-metered solar installations is 1 MW for commercial, 20 kW for residential. However, for residential systems between 10 kW and 20 kW, a utility is allowed to apply to the State Corporation Commission to impose a “standby” charge on those customers.

Seizing the opportunity, Dominion won the right to impose a standby charge of up to about $60 per month on these larger systems, eviscerating the market for them just as electric cars were increasing interest in larger systems. (SCC case PUE- 2011-00088.) Legislative efforts to roll back the standby charges were unsuccessful, and more recently, Appalachian Power instituted even more extreme standby charges. (PUE-2014-00026.)

The standby charges supposedly represent the extra costs to the grid for transmission and distribution. In the summer of 2013, in a filing with the SCC (PUE-2012-00064, Virginia Electric and Power Company’s Net Metering Generation Impacts Report), Dominion claimed it could also justify standby charges for its generation costs, and indicated it expected to seek them after a year of operating its Solar Purchase Program (see discussion below). As far as I can tell, it hasn’t carried out this threat yet, and it would likely need legislation to do so.

A bit of good news for residential solar: homeowner association bans on solar are largely a thing of the past

Homeowner association (HOA) bans and restrictions on solar systems have been a problem for residential solar. In the 2014 session, the legislature nullified bans as contrary to public policy. The law contains an exception for bans that are recorded in the land deeds, but this is said to be highly unusual; most bans are simply written into HOA covenants. In April of 2015 the Virginia Attorney issued an opinion letter confirming that unrecorded HOA bans on solar are no longer legal.

Even where HOAs cannot ban solar installations, they can impose “reasonable restrictions concerning the size, place and manner of placement.” This language is undefined. The Maryland-DC-Virginia Solar Energy Industries Association has published a guide for HOAs on this topic.

Third-party ownership of renewable energy facilities could open the market, but Virginia utilities won’t step aside

One of the primary drivers of solar installations in other states has been third-party ownership of the systems, including third-party power purchase agreements (PPAs), under which the customer pays only for the power produced by the system. For customers that pay no taxes, including non-profit entities like churches and colleges, this is especially important because they can’t use the 30% federal tax credit to reduce the cost of the system if they purchase it directly. Under a PPA, the system owner can take the tax credit and pass along the savings in the form of a lower electricity price.

In 2011, when Washington & Lee University attempted to use a PPA to finance a solar array on its campus, Dominion Virginia Power issued cease and desist letters to the university and its Staunton-based solar provider, Secure Futures LLC. Dominion claimed the arrangement violated its monopoly on power sales within its territory, under that same §56-577(A)(6) we previously discussed. Secure Futures and the university thought that even if what was really just a financing arrangement somehow fell afoul of Dominion’s monopoly, surely they were covered by the exception available to customers whose own utilities do not offer 100% renewable energy.

Yet the threat of prolonged and costly litigation was too much. The parties scuttled the PPA contract, though the solar installation was able to proceed using a different financial arrangement.

After a long and very public fight in the legislature and the press, in 2013 Dominion and the solar industry negotiated a compromise that specifically allows customers in Dominion territory to use third-party PPAs to install solar or wind projects under a pilot program capped at 50 MW. Projects must have a minimum size of 50 kW, unless the customer is a tax-exempt entity, in which case there is no minimum. Projects can be as large as 1 MW. The SCC is supposed to review the program every two years beginning in 2015 and has authority to make changes to it.

Appalachian Power and the electric cooperatives declined to participate in the PPA deal-making, so the legal uncertainty about PPAs continues in their territories. In June of this year, Appalachian Power proposed an alternative to PPAs that does not offer anything like a viable solution. The matter is before the SCC. The case is No. PUE-2015-00040. An evidentiary hearing is scheduled for September 29, 2015.

Meanwhile, Secure Futures has developed a third-party-ownership business model that it says works like a PPA for tax purposes but does not include the sale of electricity, and therefore should not trigger a challenge from Appalachian Power or other utilities. Currently Secure Futures is the only solar provider offering this option, which it calls a Customer Self-Generation Agreement.

Tax exemption for third-party owned solar may prove a market driver

In 2014 the General Assembly passed a law exempting solar generating equipment “owned or operated by a business” from state and local taxation for installations up to 20 MW. The law now classifies solar equipment as “pollution abatement equipment.” Note that this applies only to the equipment, not to the buildings or land underlying the installation, so real estate taxes aren’t affected.

The law was a response to a problem that local “machinery and tools” taxes were mostly so high as to make third-party PPAs uneconomic in Virginia. In a state where solar was already on the margin, the tax could be a deal-breaker.

The 20 MW cap was included at the request of the Virginia Municipal League and the Virginia Association of Counties, and it seemed at the time like such a high cap as to be irrelevant. However, with solar now becoming increasingly attractive economically, Virginia’s tax exemption is turning out to be a draw for solar developers. We are told Amazon’s 80 MW solar farm will proceed in four stages, indicating a desire to work around the cap—and suggesting that the tax exemption may have been a factor in the choice of Virginia as the project’s location.

Dominion “Solar Partnership” Program suggests distributed solar might be better left to the private sector

In 2011, the General Assembly passed a law allowing Dominion to build up to 30 MW of solar energy on leased property, such as roof space on a college or commercial establishment. The SCC approved $80 million of spending, to be partially offset by selling the RECs (meaning the solar energy would not be used to meet Virginia’s RPS goals). The program has resulted in several commercial-scale projects on university campuses and corporate buildings. Unfortunately, it has also been plagued by delays and over-spending.

The program was supposed to proceed in two phases, with 10 MW in place by the end of 2013, and another 20 MW by December 31, 2015. However, the program got off to a very slow start. In August of 2014 the company acknowledged it was behind schedule and would likely not achieve more than 13 or 14 MW of the 30 MW authorized before it ran out of money. On May 7, 2015 Dominion filed a notice with the SCC that it needed to extend the phase 2 end date to December 31, 2016, and confirmed that it would install less than 20 MW altogether.

Dominion’s Solar Purchase Program: bad for sellers, bad for buyers, and not popular with anyone

The same legislation that enabled the Community Solar initiative also allowed Dominion to establish “an alternative to net metering” as part of the demonstration program. The alternative turned out to be a buy-all, sell-all deal for up to 3 MW of customer-owned solar. As approved by the SCC, the program allows owners of small solar systems on homes and businesses to sell the power and the associated RECs to Dominion at 15 cents/kWh, while buying regular grid power at retail for their own use. Dominion then sells the power to the Green Power Program at an enormous markup.

I’ve ripped this program from the perspective of the Green Power Program buyers, but the program is also a bad deal for most sellers. Some installers who have looked at it say it’s not worth the hassle given the costs involved and the likelihood that the payments represent taxable income to the homeowner. There is also a possibility that selling the electricity may make homeowners ineligible for the 30% federal tax credit on the purchase of their system. Sellers beware.

And then there’s the problem that selling the solar power means you aren’t powering your home or business with solar—which is the whole point of installing it, right?

Dominion’s Renewable Generation tariff for large users of energy finds no takers; Amazon votes with its feet

Currently renewable energy projects are subject to a size limit of 1 MW. These limitations constrain universities, corporations, data centers, and other large users of energy that might want to run on wind or solar. On top of this, the utilities’ interpretation of Virginia law prohibits a developer from building a wind farm or a solar array and selling the power directly to users under a power purchase agreement.

In 2013, Dominion Power rolled out a Renewable Generation Tariff (PUE-2012-00142) to allow customers to buy larger amounts of renewable power from providers, with the utility acting as a go-between and collecting a monthly administrative fee.

From the start the program appeared flawed, cumbersome and bureaucratic, and as far as we know there have been no takers. Amazon Web Services chose to contract directly with a developer for the 80 MW solar farm it announced this year (avoiding Dominion’s monopoly restrictions by selling the electricity directly into the PJM market).

2015 marks Dominion’s foray into utility-scale solar

Late in 2014, Dominion signaled an interest in building utility-scale solar in Virginia. In 2015, at the utility’s behest, two bills promoted the construction of utility-scale solar by declaring it in the public interest for utilities to build solar energy projects of at least 1 MW, and up to an aggregate of 500 MW. At the solar industry’s urging, the bill was amended to allow utilities the alternative of entering into PPAs for solar power prior to purchasing the generation facilities at a later date, an option with significant tax advantages.

Dominion’s first solar project is expected to be a 20 MW solar farm in Remington, Virginia. The proposal is before the SCC (PUE-2015-00006). Dominion proposes to build and operate the facility itself, which will earn it a return on investment but give up tax advantages that would save money for ratepayers.

On July 17, Dominion issued a Request for Proposals for third party bidders to develop up to 20 MW of additional projects. The RFP came with an absurdly short deadline, surely limiting the number of good responses, but developers are nonetheless hopeful the results will be strong enough to convince Dominion to follow it with a larger request.

2015 will be another year without a wind farm, but there is hope

No Virginia utility is actively moving forward with a wind farm on land. For the past few years, Dominion Power’s website has listed 248 MW of land-based wind in Virginia as under development, without any noticeable progress. There has been a lot of press about the current standoff in Tazewell County, where supervisors are blocking Dominion’s proposed wind farm. Yet Dominion’s advocacy for its project feels perfunctory. The company has signaled it prefers solar, and its 2015 IRP dismisses wind as too costly. On the other hand, Appalachian Power’s IRP suggests an interest in wind as a low-cost renewable resource that could help it meet the Clean Power Plan.

With no utility buyers, Virginia has not been a friendly place for independent wind developers. In previous years a few wind farm proposals made it to the permitting stage before being abandoned, including in Highland County and on Poor Mountain near Roanoke.

As of 2015, however, Apex Clean Energy is in the development stages for a wind farm of up to 80 MW in Botetourt County. No customer has been announced, but the company believes the project can produce electricity at a competitive price.

As for Virginia’s great offshore wind resource, the perception that offshore wind energy will be costly continues to hold back progress. In 2013 Dominion won the federal auction for the right to develop about 2000 MW of offshore wind power, and the lease terms call for the company to file construction plans within five years. The federal government’s timeline leads to wind turbines being built off Virginia Beach around 2020. As I’ve discussed elsewhere, Dominion is something less than committed to seeing the process through. This puts advocates in the legislature and in the business and environmental communities in the odd position of being keener on a development than the developer is.

Meanwhile, however, Dominion is part of a Department of Energy-funded team designing a pilot project of two 6-MW offshore wind test turbines, originally scheduled for installation in 2017. This year Dominion declared it was taking a “step back” when the sole bid for the contract came in way too high. Stakeholders have been meeting this summer to help chart a path forward.

Will a Solar Development Authority help?

One of the MacAuliffe Administration’s initiatives this year was a bill to establish the Virginia Solar Development Authority. The Authority is explicitly tasked with helping utilities find financing for solar projects; there is no similar language about supporting customer-owned solar. The Authority is supposed to identify barriers to solar, but isn’t given any tools to remove them. The Authority has not been given funding. And members have not been named yet. Meanwhile, the clock is ticking on that December 31, 2016 expiration of the 30% federal tax credit.

The Clean Power Plan: better to switch than fight

On August 3, 2015, EPA issued the final rule known as the Clean Power Plan. Under the rule, states with existing fossil-fuel generating plants must develop plans to reduce total carbon pollution from power plants. In Virginia, the task will fall to the Department of Environmental Quality.

While Virginia’s goals under the plan are modest, the rule means the state, utilities and the SCC must for the first time take carbon emissions into account in their planning. The EPA has signaled a strong interest in seeing wind and solar deployed as solutions.

Some legislators have succumbed to partisan pressure to attack the Clean Power Plan, using talking points provided by fossil fuel front groups. Not only does this do a disservice to Virginians already suffering the effects of climate change, it’s bad economic policy. EPA’s analysis shows Virginia is already on track to meet or come close to our Clean Power Plan goals. Wasting time fighting the plan, or mandating that utilities keep outdated coal plants open, makes far less sense than using the plan as a catalyst to begin an efficient and cost-effective energy transition.

The transition need not even happen fast, as EPA’s numbers suggest that all we need to do is keep our total carbon emissions from increasing over time. Energy efficiency has a huge role to play in achieving this, but so would a requirement that utilities meet any increases in electrical demand with wind and solar. Freeing up the private market will go a long way towards achieving that goal. And of course, when customers install solar “behind the meter,” it keeps electric demand from growing.

The Department of Environmental Quality will be holding “listening sessions” this fall to take public comment prior to developing a state implementation plan under the rule.