Photo by Dennis Schroeder / NREL

Congress included a welcome gift to the wind and solar industries in last week’s package of goodies that made up the year-end spending bill. For the wind industry, the renewal of the expired production tax credit (PTC) with a five-year phase-out finally ends the guessing game that has driven repeated boom-and-bust cycles—and will help Virginia’s first-ever wind farm move forward.

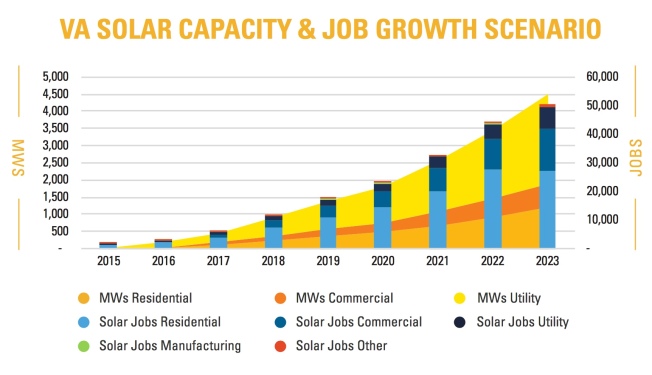

For solar, the extension of the investment tax credit (ITC) beyond the end of next year ensures that one of the fastest-growing industries in the U.S. won’t face a major disruption that would have driven many small companies out of business. That’s critical in Virginia, where the lack of incentives has left the market mostly to small players able to get by on small profit margins. As the economics of solar continuously improve, these small companies see a bright future in the Commonwealth.

I asked several Virginia industry members how they were feeling after Congress’ year-end gift.

“The certainty the tax credit extension gives our business is critical,” answered Jeff Nicholson, Director of Development for Waynesboro-based Sigora Solar. “While there won’t be as much of a crunch to get systems installed next year, we can hire without being concerned that the market for solar will plummet in a year.”

Sigora has been one of Virginia’s most remarkable small business success stories, growing from 11 employees at the beginning of 2015 to 44 today. With the ITC extension, the company now foresees a “long-term, steady stream of business” through the rest of the decade, said Nicholson.

The 30% ITC had been set to expire at the end of 2016 for residential customers, while dropping to 10% for commercial and utility-scale projects. Under the bill passed by Congress and signed by President Obama on December 18, the tax credit will remain at 30% for all systems through 2018, and then taper off gradually until it reaches 10% in 2022. If current price trends continue, the extra few years may be enough to make solar competitive with other fuels without subsidies.

“We know solar is a solid energy production fuel, every bit as viable as coal, oil, nuclear and wind, and it is clear that the more we build, the more cost effective it becomes,” said Paul Risberg, President of Charlottesville-based Altenergy Incorporated. Altenergy grew by 40% in 2015, and Risberg told me he now expects that trend to continue in 2016.

Another Virginia success story is Staunton-based Secure Futures LLC, which has carved out a niche supplying solar energy to tax-exempt entities like universities and local government entities in Virginia, using third-party power purchase agreements. CEO Tony Smith told me, “The ITC extension means that our business can continue to offer at or below grid-parity solar electricity to our commercial scale customers beyond 2016.”

But, he added, “It still remains challenging to attract investment in Virginia due to the disparity in incentives to solar in our state as compared with our neighboring states, especially for behind-the-meter third party owned solar. We remain hopeful that our industry will continue to build support in Richmond to reduce the barriers to solar investment in Virginia.”

The Virginia solar industry got an extra year-end gift on Monday when Governor Terry MacAuliffe announced plans for the state government to buy 110 megawatts of solar over the next three years, accounting for 8% of its electricity usage. While 75% of that will be utility-scale solar to be built by Virginia Dominion Power, 25% will consist of on-site projects of less than 2 megawatts in size, to be built by third-party developers using power purchase agreements.* The state will follow a competitive procurement process, but in response to a question at the press conference, MacAuliffe said it will not limit participation to Virginia-based companies.

Still, the Virginia industry members were optimistic the announcement would help boost the profile of solar energy in the Commonwealth. The industry trade group, MDV-SEIA, says it participated in the discussions leading to the announcement.

Virginia has a lot of catching-up to do, of course; neighboring states are so far ahead and have so much momentum that, as the Virginia Sierra Club’s Glen Besa observed, “If Dominion sticks to its commitment (of 400 megawatts of solar by 2020), we’ll be further behind on solar than we are now.”

Photo credit NREL

Like the ITC for solar, the 2.3 cents per kilowatt-hour PTC has been a crucial support for the wind industry, making it the second-biggest source of new electric generation in the U.S. for many years now. But until last week, Congress had been reluctant to extend the PTC for more than a year at a time, sometimes retroactively, causing havoc for planners and developers and leading to boom-and-bust cycles deeply damaging to growth.

Now the PTC will be extended through 2016 before tapering off and expiring altogether at the end of 2019. Projects that “commence construction” by the end of a given year will qualify at that year’s level. (“Commence construction” language was also added to the solar ITC.) The predictability that comes with the five-year tapering-off period is expected to finally bring stability to project planning.

And like the solar industry, the wind industry now predicts bright days ahead. Bruce Burcat, Executive Director of the Mid-Atlantic Renewable Energy Coalition, told me, “Sound policies like the PTC have driven innovation which has helped reduce the cost of wind energy down by about 66 percent over the past six years, making it highly price competitive with traditional forms of energy resources. This trend bodes well for the opportunity for wind to take hold in Virginia.”

Burcat is undeterred by Virginia’s lack of success with wind farms to date. “While no wind farms have been developed in Virginia, we believe that with the right signals from the Commonwealth, Virginia could see its first wind farms developed sometime in the next few years,” he said. “Wind farms would bring investment and jobs and other economic development opportunities to Virginia. Wind farms would also be a very important tool for cleanly and cost-effectively helping Virginia meet the requirements of the EPA’s Clean Power Plan.”

Virginia’s first wind farm is expected to be Apex Clean Energy’s 75-MW Rocky Forge project in Botetourt County, which the company projects to have operational in 2017. Tyson Utt, Apex’s Director of Development for the Mid-Atlantic, told me, “The extension of the PTC will enable the facility to charge less for the energy it produces, saving electricity consumers money.” And, he added, “The project will be built on private land with private investment and will help diversify Virginia’s energy mix while injecting millions into the local economy.”

Apex also has a second wind farm of up to 180 MW under development in Pulaski County, scheduled for completion in 2017 or 2018.

Utt agrees the wind industry won’t need incentives for long to compete with fossil fuels. “The PTC exists to help level the playing field for renewable energy, relative to legacy generation sources that have benefited from permanent subsidies for decades. That said, renewable energy is becoming so economically competitive on its own that the industry now feels comfortable accepting a phase out of the PTC over the next five years, and the tax extenders package that just passed through congress does exactly this. Of course, wind energy offers additional benefits that are not currently reflected in our incentive structure, including the ability to generate electricity without producing carbon dioxide or consuming water. We expect that as our nation moves towards the recognition that there should be a price placed on carbon, wind energy will become even more competitive with conventional generation sources.”

[UPDATE: on January 6, the Associated Press reported that Appalachian Power is seeking to buy up to 150 MW of wind power through direct ownership or long-term power purchase agreements.]

In addition to the tax credit extensions for wind and solar, Congress passed other clean energy incentives that have gotten less attention. Scott Sklar, President of the Arlington-based Stella Group, Ltd. and an adjunct professor at George Washington University, noted that other renewable technologies also qualified for tax credits, and a tax deduction for energy efficiency improvements in commercial buildings was renewed. He also pointed to provisions in the Highway Authorization Act passed into law this month that favor renewable energy. As a result, he told me, “The end-of-year passage by Congress of extensions for the entire portfolio of energy efficiency and renewable energy, coupled with the infrastructure incentives for renewable energy in the highway bill, will more than double private investment into these sectors over the next six years.”

Sklar is bullish on clean energy. “With expanding markets, allowing these technologies to-scale even further, will insure electric grid and fuel parity before 2020, and also insure that renewable energy and energy efficiency will become the dominant energy provider both in the US and the world.”

I should note, though, that not everyone was entirely happy with Congress last week. Though they lauded the tax credit extensions, environmental groups including the Sierra Club opposed the lifting of the oil export ban that Republicans demanded in return. Exporting American crude oil, they fear, will lead to more drilling in the U.S. and higher oil consumption worldwide, further driving climate change. And while wind and solar compete head-to-head with the biggest climate culprit, coal, currently they offer little competition for oil in the transportation sector.

But with a world-wide oil glut that shows no signs of easing, observers including Sklar think lifting the export ban won’t have much effect in the near term. The extension of the renewable energy tax credits, on the other hand, will help push clean energy pricing to a point where wind and solar dominate the market for new electricity generation. According to an analysis by the Council on Foreign Relations, “Extension of the tax credits will do far more to reduce carbon dioxide emissions over the next five years than lifting the export ban will do to increase them.”

So it’s easy to see coal as the biggest loser here, but Big Oil shouldn’t feel too smug. As battery storage becomes more affordable and electric cars gain market share, wind and solar will begin to displace oil, too. The future, my friends, belongs to clean energy.

Here’s to 2016!

________________________

*The astute reader may wonder how the Governor persuaded Dominion to allow it to buy electricity from third-party providers in spite of Dominion’s tireless defense of its monopoly on electricity sales and its reluctance to allow other customers to use PPAs outside the narrow confines of a pilot program. Unlike most of us, the state purchases power from Dominion under a contract, rather than under a tariff overseen by the State Corporation Commission. So allowing the state to use PPAs required negotiating a change to the contract but does not have immediate ramifications for lesser folk. But still: at some point, doesn’t it become obvious that restrictions on PPAs are simply holding the market back?

And even all you astute readers may not have thought to ask: when the state buys solar electricity from Dominion or third parties, who will own the RECs? After all, it is not the guy with the solar system on his roof who can legally claim to be using solar energy, but the guy holding the renewable energy certificates (RECs) associated with that energy. If the state wants to brag about meeting its new goal of 8% of its electricity from solar, it had better hold the RECs to prove it—and not, for example, allow Dominion to sell the RECs to a Pennsylvania utility or to the voluntary participants of its Green Power Program. When I asked Deputy Secretary of Commerce Hayes Framme about this, however, he said the question of who will own the RECs “has yet to be determined.”